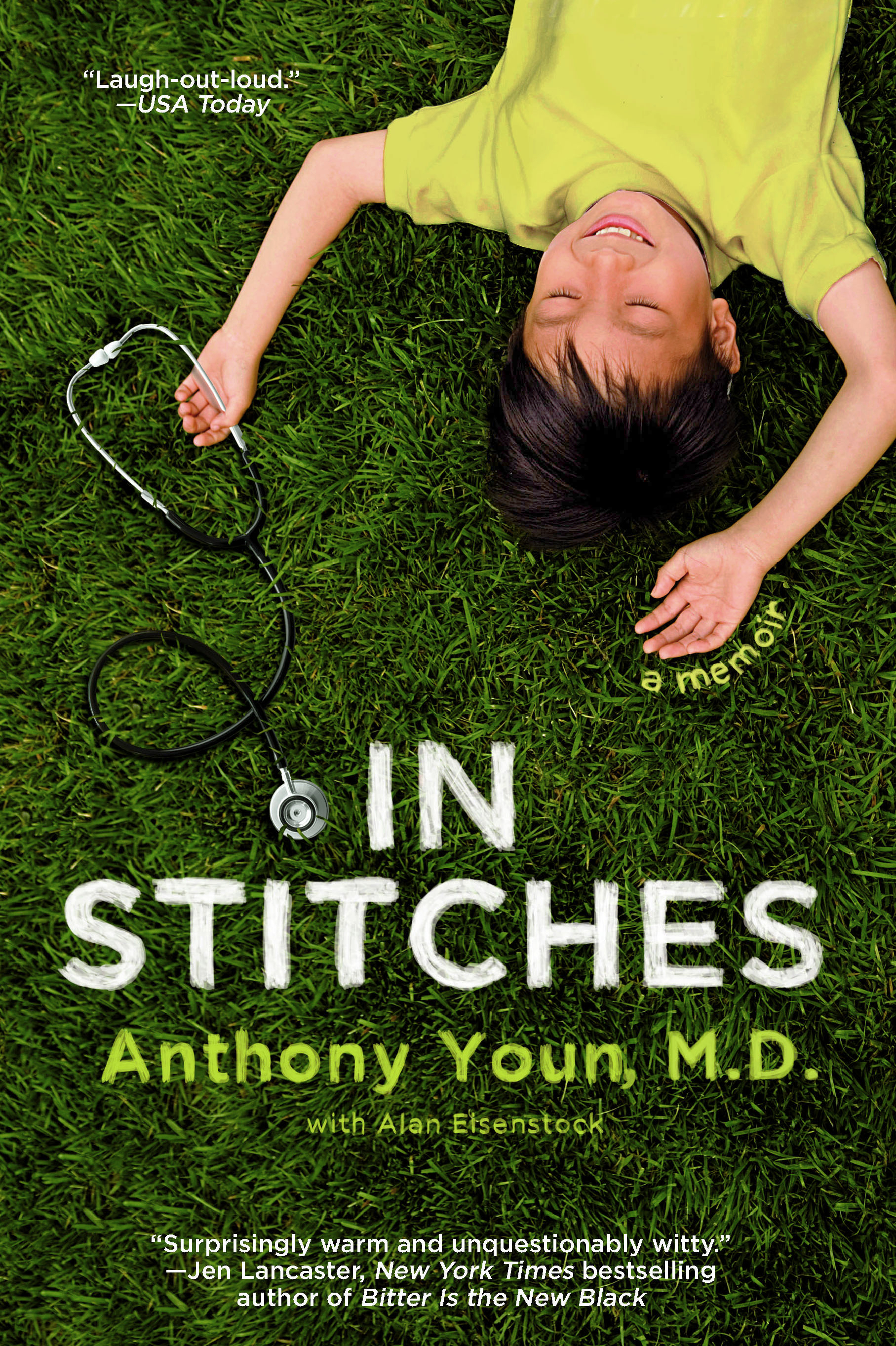

Deleted Scenes

Deleted Scene: “Little People, Little Dollah!”

Third year.

I’m deep into my final clinical rotation: Pediatrics. Peeds, for short. Not my favorite. Or as my dad says, “Little people, little dollah!” But that’s not why I don’t love pediatrics. Treating a child is like treating Fido. The patient has no clue why he or she is here. Why is that mean person in the white coat hurting me? And after the mean person in the white coat hurts me, why does he give me a sticker or a milkbone?

Today I have the joy of spending nine hours straight in the outpatient pediatrics clinic. Hour six. My thirtieth patient of the day arrives. Timmy. A three-year-old linebacker with a blond Mohawk. And he doesn’t exactly arrive. His mom carries him in, kicking, screaming, scratching, and howling. Par for the course. I’ve spent this entire rotation wrestling three-year-olds to the ground so I can look into their ears with my otoscope. Fun. And because I’m both obsessive and curious, I’ve kept track of the number of patients I’ve seen and/or wrestled during the rotation so far. Timmy makes 531.

I size Timmy up. He snarls, lunges. I back up. I’m not worried. I’m pretty sure I can take him. Pretty sure. He does have an advantage. He’s built low to the ground and he has long nails. His hands look like claws. I wonder if he has a lot of teeth. The last kid I went for sank his baby teeth into my forearm and locked his mouth there for thirty seconds before I could escape. My arm looks like a pin cushion.

Most medical students choose pediatrics because they love kids. At least that’s my guess. And most pediatricians are by nature calm, nurturing, and nonviolent. They start by trying to connect to the kids on their level. Meaning, bribery. They wear dorky cartoon-character ties and offer sheets of stickers up front. They tell corny jokes that the kids hate. They talk in high pitched cartoon voices, which usually scare the kids rather than soothe them. As a last resort, they lie. They tell the kid that Mickey Mouse has moved inside the kid’s head and Doctor Happy wants to look at Mickey and Minnie’s new condo.

Like any kid is going to buy that. Especially a kid like Timmy who resembles a midget ultimate fighter. No way I’m going the Mickey Mouse route.

“Okay, Timmy,” I say, bending over him with my otoscope. “I’m going to find Nemo now. Did you know he just moved inside your head?”

He slams his palms over his ears.

He glares at me. I regret the Nemo move. Fair enough. The idea of a Disney character lodged inside my skull would freak me out, too, even more than knowing I had an infection. I decide to go for total honesty.

“Timmy, okay, Nemo does not live inside your skull. Nobody does. All I’m going to do is take a quick look inside your ears to make sure that you don’t have any bad yucky gross gunk growing in there, okay?”

I step toward him.

He backs up.

I move left, he goes right. I circle right, he spins left. I fake left, go right.

Pay dirt.

I take him down. I scramble for my otoscope. Timmy squirms, but I’ve got him pinned.

Wait a minute? Have I lost my mind? What am I doing? He’s three.

So I’m straddling three-year-old Timmy’s chest. Somehow I manage to squirrel over and peer into each of his ears.

Pink.

Damn. I was hoping for either beige or lobster red so I could call his ears clear or infected. Now I’m undecided. Worse, the glance into each of Timmy’s ears leaves me vulnerable. He grabs my stethoscope, holds it up to his mouth, and screams. My eardrums explode. I howl and loosen my grip. That’s all the daylight Timmy needs. He wriggles away and streaks toward the door. I reach from the floor, a conga drum sound pounding inside my head—bambada bam bambada baaaa—snag Timmy’s ankle and reel him back in.

“Timmy, I just want to see if you’re all right,” I say, the words banging against my head like a rap song. “I want, to, check, your, vital signs. It won’t hurt a bit. I promise.”

I try a reassuring grin.

Timmy growls and kicks me in the throat.

“Grrragh,” I moan. I fold my arms under his knees and wrestle him back down.

“Fun times, huh?” I say. “Okay, I’m going to count your heartbeats. You want to count with me?”

“MOMMMMY!”

“You’re hurting him.” A tortured voice from across the room.

“I think it’s the other way around,” I say.

“He’s three.”

“I doubt that,” I mutter. “Kid’s a midget wrestler. A pro.”

I try my best then to hear his heart and lungs. Between Timmy’s wailing and the mom’s repeated complaints, I can’t hear a thing. I try to locate his pulse. Can’t. Resigned, I lean back and look at Timmy. The kid certainly seems lively, no sign of lethargy, even though I can’t track any vitals. At least not yet. I won’t give up. Two reasons. First, I’m in medical school and I’m extremely conscientious, bordering on dogged. Second, I don’t want to get marked down.

“Tell you what. Let’s take a five. Go to our neutral corners. Then you let me listen to your heart and lungs. Because if you don’t, I’m not allowed to give you a Lightning McQueen sticker when you leave.”

Timmy glowers. He stands at attention and gives me a serial killer stare. Then he sneaks the ace out of his sleeve. He drops his pull up, grins, and grunts.

“What? Oh, no. NO!” I yell.

“Timmy, don’t! Timmy!” The mom skids into view, her arms flailing toward Timmy’s tossed away training pants.

Too late.

Code brown. Boom. Right on the exam floor.

Checkmate.

I lose.

Peeds.

And poos.

Yeah, forget pediatrics.