Christmas From Hell

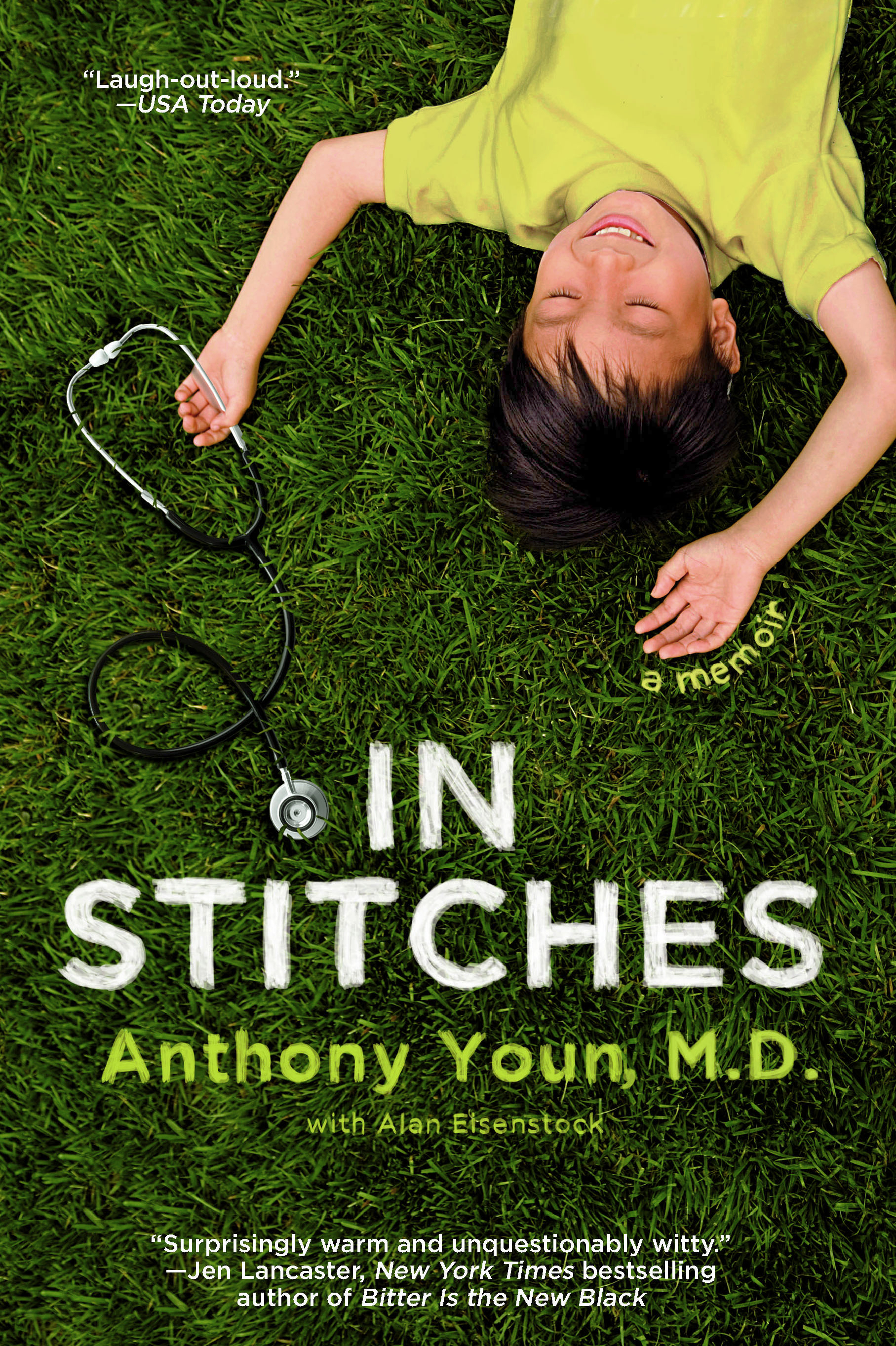

Excerpt from In Stitches by Dr. Youn

My first Christmas home from college.

The Christmas from hell.

First semester, over and done. I can’t wait to chill out at home. See friends. Go to parties. I even entertain thoughts of hooking up with Janine. Desperate men do desperate things.

My brother came home from Northwestern a day earlier. When I walk into the dining room and see Mike’s face, I know we’ve got a problem.

“Dad wants to talk to us.”

“About what?”

He shrugs, drums his fingers on the oak tabletop. If he knows, he’s not saying. I don’t press him. We sit without speaking for ten achingly long minutes until my parents arrive in the dining room. My father nods at my mother, steps farther into the room, leaves her framed in the doorway. “Your brother,” my father says to me.

A lump rises into my throat. Mike must be sick. I look at him. He looks down. I turn to my father. “What’s wrong?”

“Look.” My father slides a sheet of paper toward me. It flutters against my outstretched hand.

I pick up the paper and start to read: Northwestern University Official Transcript. I hand the paper back to my father. “This is none of my business. These are Mike’s grades.”

“No. Read. Please.”

I hesitate, then reluctantly scan the transcripts. One A, the rest B’s. I look helplessly at Mike. I don’t know why I’m here, why I’ve been included in what should be a private conversation between Mike and my father. Mike stares straight ahead. He looks numb.

“Your brother,” my father says, “has shamed the family.” He lowers his voice, speaks solemnly. “How can he become a doctor with grades like these? No way. Impossible.”

Normally, at this point, my brother would stand up to my father. But today, a week before Christmas, he doesn’t fight at all. He seems defeated.

“Michael, how?” My father leans back, then shoots up both hands in surrender. “How you get into med school? You need to study. Both of you.”

I blink, not understanding.

“You don’t study?” my father says, his voice rising. “You can’t become a doctor. You end up bum on the street. You have to study every day. Christmas, too.”

“I’m sorry,” I say. “I’m not sure what’s happening here. We finished school. Took our finals. We don’t have anything to study.”

My father pulls out a chair. On the seat, he has placed a stack of MCAT-prep books. Each one weighs in at three hundred pages, minimum. “You study these. MCAT prep.” My father holds, waiting for the fight in Mike to come out.

Mike shakes his head, amazed, stunned. I try a tiny laugh to soften the moment. “You mean a couple hours a day—”

“No, no,” my father says. “All day, every day. Otherwise—” A massive helpless shrug aimed at my mother. She nods sadly from the doorway. None of this is making sense. I look at my mother to get my bearings. She stares back, her mouth flat-lined in compliance. I look back at my father. “I thought we were going to L.A. for Christmas to see Grandma. We have plans, plane tickets—”

“No more,” my father says. “Not going to L.A. Not this year. This year you boys study. Very important. This year Daddy cancel Christmas.”

Mike swears under his breath. He jerks a book out from the middle of the pile, causing the rest of the stack to topple and crash onto the floor. My father flinches slightly but shows no other reaction. Mike opens his book in slow motion, drops his chin an inch above the page, and starts to read, moving his lips. My father pivots and walks out of the room, my mother at his heels. Mike and I look at each other and then, the dutiful sons, now prisoners, begin silently reading, studying for the MCAT.

Every morning after breakfast, Mike and I return to our bedroom and hit the books. Or so my father thinks. We alternate standing watch, two-hour shifts each, while the other lies in bed dozing, reading comic books, or listening to music. In reality, we study not at all. At times when my father surprises us with a random check-in, I force myself awake, spin the book around on my chest, hoping it’s not upside down, and pretend to be glued to the page. We take half-hour breaks for lunch and dinner, then “study” into the night until my father dismisses us. My mother and sister do fly to L.A. for a shortened Christmas holiday. On Christmas Day, my father goes to a friend’s for dinner. Mike and I microwave hot dogs and sneak some TV until we hear my father’s car in the driveway. We shut off the set, shove the dogs in the trash, and hustle upstairs, taking our positions in our beds, eyes trained on our MCAT books.

In those two weeks, during the moments when I daydream—and I daydream a lot—I think about my father on the farm in Korea. I imagine how hard he must have worked and how disciplined he must have been to escape from that dirt-poor farm overrun with eight brothers and sisters, not an inch of space for privacy or study, and while I want to hate him for killing my Christmas, ruining my winter break, and humiliating my brother, I can’t. It’s crazy, but I feel a rush of respect for him. I’m also royally pissed and so antsy that I’m jumping out of my skin and embarrassed beyond words to tell my friends the truth, that I’m stuck home studying because my brother bombed his grades and my dad freaked out.

But what the hell. Here I am. I have no other choice. I might as well accept my fate and embrace it. Yes, I’m locked away. But you can’t really call this prison. I’m in my room, all the snacks and soda I want, hanging out with my brother, whom I love, and with whom I’ll laugh about this someday. It could be worse. For my father, it was worse.

The afternoon of New Year’s Eve, my father releases us from our room. I quickly patch together a sketchy New Year’s Eve plan and head off for some party in hopes of finding Janine, which doesn’t happen. My brother, sullen, vague, talks about attending a party with some friends, but he doesn’t really seem into it and stays home.

Three days later, my backpack riding shotgun in the fussy Ford Tempo, I return to Kalamazoo College to my dorm, my suite-mates, my group of nerd friends, and no women, no women at all.

Before I leave, my father announces that he has transferred my brother to Kalamazoo College and moved him into a dorm not far from mine. What I know in my heart but dare not utter is that no matter how many MCAT books my father forces him to study and how many Christmases my father cancels, my brother will never become a doctor.